Dean Kissick

NOT LONG AGO, every time I went to my Instagram Explore Page, I’d be shown a grid full of photos of dark-haired girls doing things–fine–and, in the top-right corner, a larger video of someone called “Charli D’Amelio” dancing on TikTok. I didn’t know who this girl was, but took an immediate dislike to her face, her general countenance, the way she moved, her aura, and so I’d always open the dropdown and ask not to be shown any more content like this; please, not this.

The next day there’d be another video of her, and I’d ask not to be shown any more content like that either. The next day: more Charli. The day after: Charli. This went on for weeks, before history eventually overtook her (I’m now shown a link to an AAPI Anti-Racism Resource Guide).

So, there are a couple possibilities here: either I’m obsessed with Charli D’Amelio but haven’t yet realized it, am repressing the dark tell-tale side of my heart, and the algorithm understands my weak and penitent flesh better than I do myself; or else Instagram doesn’t have much of an idea of who I am, or what I want, and refuses to learn when I repeatedly tell it. And so: I don’t trust the corporations writing these broken algorithms, to be in charge of the largest automated censorship operation in history. And for more than a decade now, it’s been through these social networks that our experience of reality is created.

Friends have been shadowbanned lately: which is to say, their content has been restricted and they haven’t been informed of this. It happens, like other forms of deplatforming, quietly, in a cloud of fuzzy, arbitrary rules that can easily be exploited, and are enforced by a combination of black-box algorithms and content moderators working at breakneck pace. Those who are shadowbanned aren’t told that they are. Those who are suspended are told, but aren’t told why. Nor are they provided with a right to appeal. No one can see what they’ve done wrong either; but how are we supposed to know which lines not to cross, if they’re never shown to us? Does anyone, including those working for these companies, really know where those lines are? The best accounts always disappear in the end. And so does everything they’ve ever said.

These bans may be a part of a sinister plot, or may just be the result of a collection of malfunctioning algorithms. But even if the latter is the case, it also provides a convenient excuse. Can you recall the great political purge of January? Remember when Trump was banned for life from Pinterest? During that purge, a variety of socialist pages, like the International Youth and Students for Social Equality page for the University of Michigan, were disappeared from Facebook. Later, following a public outcry, the company explained that this had only happened because of an “automation error.” But what kind of an excuse is that? “It wasn’t us; it was just our totalitarian automated censorship matrix that malfunctioned.”

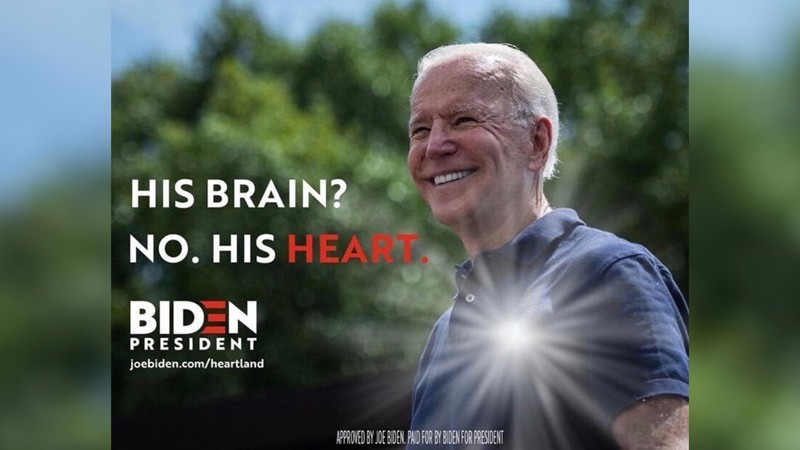

If you look at the history of the world, outside of wartime, those pushing censorship were never really the good guys (a common exception is Socrates, who believed poets and storytellers should be censored so that they didn’t corrupt the youth; however he was also himself sentenced to death by poisoning for corrupting the youth). When social media giants are currying favor with Joe Biden and his administration, it’s not because they endorse his policies, it’s because it’s good for business; and, more to the point, because he’s one of the only figures in the entire world who might, possibly, have the means to curtail their immense power. He may be one of the very last men with the means to do so.

Mark Zuckerberg has more power and influence than anyone that’s ever lived. He rules over a far more expansive empire than his idol, the first Roman Emperor Augustus, and his manipulative powers are hard for us to make sense of, because we’ve never encountered anything like them before. This century’s new media moguls have great powers of surveillance, and powers also to suppress speech, and so to push narratives, and manufacture consent. Given that we can no longer assume a sense of privacy, surely the least we’re owed in return is visibility? Wasn’t that the great contract?

Since the turn of the century there have been warnings that the free internet would be gated by corporations. The Noughties brought the enclosure of the commons by tech giants, while the 2010s brought much more policing of the public by those giants. But at the same time, we have also voluntarily begun to gate the net ourselves. 2017 and 2018 brought the wholesale abandonment of Facebook by Millennials, in favor of more private and impermanent forms of communication like the small group chat and the finsta (pseudonymous “fake Instagram” account); but conversely, this was also when TikTok exploded in popularity among a younger generation. 2019, so far as I can recall, was a great year for subreddits. The big media trend of 2020, a time of pure hysteria, was the rise of paid, or invitation-only, Discord servers and other big group chats on WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, and Slack; and side-chats where you complained about people in the group chat; and subscription-only Substack mailouts, Patreon podcasts and OnlyFans pages; and Close Friends Instagram Stories, which came into their own during lockdowns when many wished to keep their lives and indiscretions more private. It was a year of fragmented content, and of slipping away into the internet’s Dark Forest.

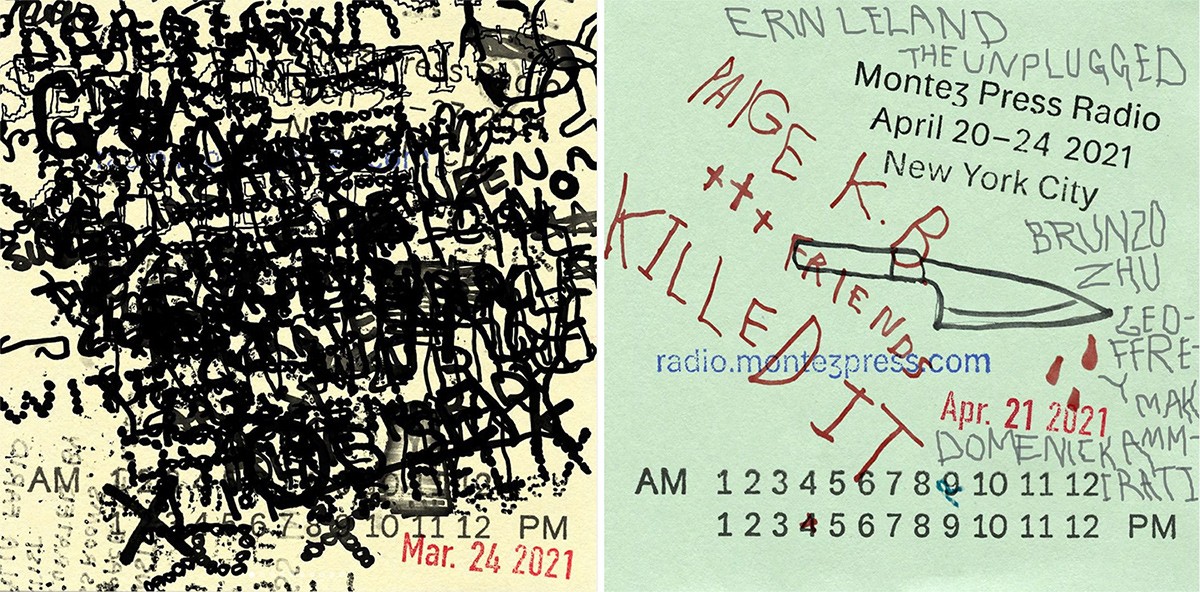

Over the past year in Manhattan, attention has also been lavished on short-run, scene-specific print newspapers like Civilization and the Drunken Canal, and magazines like Dirty, which go a step further and don’t publish anything online, as well as to platforms like Montez Press Radio, which broadcasts live but is otherwise hard to listen to. Hans Ulrich Obrist used to always say that it’s important for an artist to create a “rumour”. He’d circumnavigate the globe, chasing after rumours. Likewise, in an age of too much of everything, it makes a twisted kind of sense to publish a paper that few can ever read, or craft ambitious, obtuse radio shows that fade away into the waves. You can will your own scene into being by hyperstition; and once you have, can communicate with it directly through, like Drunken Canal, Close Friends Stories that lead to events, or, like Civilization, complicated metaphysical maps of everyone you’ve ever met Downtown. In cases like these, ideas from the gated internet are brought back into the real world to amuse, or annoy, everyone else. Sometimes readers are so frustrated that they print their own response paper; which raises the enticing prospect of a return to an 18th-century model, with the presses ever-whirring and everyone constantly publishing their own pamphlets slandering one another.

When I spoke to Ben Smith, the New York Times media reporter who wrote the big story about these papers (“They Had a Fun Pandemic. You Can Read About It in Print”), he made the interesting point that this new Downtown alternative media scene is quite anti-careerist, compared to, say, the old n+1. On the other hand, staying outside of legacy media and traditional publishing formats and just making a name for yourself and your friends is probably the best thing you could do for your career these days. This is a golden age for contrarians: just look at the most popular Substacks and the podcasts with the largest Patreons. Look at the funniest artists on Instagram. There’s a great value to, and audience for, outspokenness, irony, cynicism and sarcasm in the present, even though many will pretend that there’s not. In a moment of absurdly and comically partisan discourse, contrarianism plays an important role, and is profitable besides, and it’s where much of the action in media now flows. Making a name for yourself is the best thing you could do for your career, except it might all fall apart if you’re shadowbanned.

For the last decade or so, it’s felt like if you don’t have a social media presence, you don’t really exist. That presence can be taken away from you at any moment. However, new kinds of communities, whether they live in a Discord server, or cheap newsprint, or a pirate radio station, offer some of the support structures legacy institutions once did, while allowing you to remain independent. Now everyone is an artist; and also a community manager.

Where does identity reside? In the '80s and '90s, it was expressed through the brands we wore, the styles in which we dressed, and the music that we listened to—by consumption. In the 2010s it was expressed through the images we shared of ourselves and the opinions we displayed in public—by elaborate self-expression. A person is no longer a collection of labels and pop-cultural tastes, but rather a golem made of opinions. A Frankenstein’s op-ed page come to life, dribbling rotten takes from their mouth. You are whatever you say. You are your opinions. You were your opinions, but now we’re moving on again. Now our identities reside in our communities, and in the conversations we have with our friends, where we can express ourselves more candidly to an audience that sort of understands.

Our identities are formed in the relationships we have with others. Those relationships used to take place in public, and now they play out in private. The public sphere, Immanuel Kant thought, was made possible by printed journals, and the cafés and salons in which they were discussed. Such were the conditions in which the Enlightenment could begin. Now we have a far larger and more connected public sphere, and the Enlightenment project is being dismantled. We also have more and more communities thriving, out of sight, in the Dark Forest. These have a waning connection to each other, and the broader public sphere, but it doesn’t matter. It’s how things always used to be. It’s been a nightmare hearing everyone’s thoughts and opinions really. We don't have to live in public. We can shadowban ourselves. All we need to find are interesting people we can trust, and places we can speak without interference, free from the sick guiding hands of the attention economy.

Published: April 2021

Dean Kissick is the New York editor of Spike art magazine, for whom he pens the monthly column "The Downward Spiral." @deankissick on IG & Twitter.

Stolbun Institute is a new initiative founded by Seth Stolbun and the Stolbun Collection, which seeks to coordinate content across platforms in the face of culture sector atomization. This text will be archived as part of Stolbun Institute's Season 1: Shadowlands.